Beyond Self-Consistency: How CER Boosts LLM Reasoning by Leveraging "Process Confidence" (ACL 2025)

1 Introduction

In reasoning tasks involving Large Language Models (LLMs), we often find that while models can provide answers, it is difficult to determine whether those answers are “reliable.” The current mainstream approach in academia is Self-Consistency (SC), which involves letting the model generate multiple outputs and then selecting the answer using a “majority vote.” However, this method has a fatal flaw: it assumes that the weight of every reasoning path is equal, ignoring the model’s “hesitation” or “confidence” during the generation process.

The paper discussed in this article, CER (Confidence Enhanced Reasoning), proposes an elegant and Training-free solution. Accepted by the ACL 2025 Main Conference, its core contribution lies in proving that “Process Confidence” during reasoning is more valuable than merely looking at the “confidence of the final answer.”

Before diving into the details, let’s list the resources for this paper:

- Paper Link: arXiv:2502.14634

- Code: GitHub Repository

2 Problem Definition

Before understanding the specific solution of CER, we must first clarify: Why aren’t existing LLM reasoning enhancement methods good enough?

As the capabilities of Large Language Models grow, we are starting to task them with complex problems requiring multi-step thinking (such as mathematical proofs or Multi-Hop knowledge QA). However, LLMs are fundamentally probabilistic models, which means they inherently come with “uncertainty” and “hallucination.” To alleviate this problem, academia has developed many techniques, but they each have obvious pain points.

We summarize the challenges this paper attempts to solve into the following three points:

2.1 Limitations of Self-Consistency

The currently dominant method for improving reasoning ability is Self-Consistency (SC). Its concept is simple: let the model generate different reasoning paths for the same question, and then statistically select the most frequent answer as the final result (Majority Voting).

Although effective, this method implies a dangerous assumption: Every generated path is “equal.”

In reality, this is not reasonable.

- Scenario A: The model derives the answer through rigorous deduction with high confidence.

- Scenario B: The model is full of hesitation (low probability) during deduction but happens to stumble upon an answer.

Under the SC mechanism, the vote weight for Scenario A and Scenario B is the same. Even worse, when the model exhibits “Consistent Hallucination”—where the model confidently and repeatedly generates the same wrong answer—SC will unhesitatingly choose this wrong answer because it only looks at “quantity,” not “quality.”

2.2 Noise in Whole-Sequence Uncertainty

Since simply counting votes is problematic, shouldn’t we just introduce “Confidence” weighting? Usually, we can use the Logits output by the model to calculate the probability or Entropy of a sentence. However, directly calculating the confidence of the Whole-sequence reasoning path introduces a lot of noise.

A typical Chain-of-Thought (CoT) contains a large number of Functional Words, such as:

- “First, we need to calculate…”

- “Therefore, the answer is…”

- “Based on the assumption…”

These words are crucial for grammatical flow, and the probability of the model generating them is usually very high (high confidence). If we calculate the average probability of the entire text, these insignificant high-score tokens will dilute the truly key information (such as a critical calculation number or entity name). This makes it difficult to distinguish between a “logically correct path” and a “grammatically fluent but nonsensical path.”

2.3 Neglect of Intermediate Reasoning Steps

Complex reasoning is often “interconnected.” A math problem might require five steps; if the second step is calculated incorrectly, the final answer will be wrong regardless of how perfect the logic in the subsequent three steps is or how confident the model seems.

Many existing methods tend to only evaluate the confidence of the final generated answer. This ignores a core fact: Errors often happen in the middle.

This paper argues that to judge whether a path is reliable, we cannot just look at the destination; we must check every turning point in the process. If the model shows hesitation (high entropy, low probability) at an intermediate step, this is a strong warning sign implying that the weight of this path should be significantly reduced.

3 Methodology

The core philosophy of CER (Confidence Enhanced Reasoning) is:

Don’t look at the whole sentence, look at the key points; don’t just count heads, check confidence.

This is a completely Training-free framework; it does not require modifying model weights or using an external Reward Model. It purely utilizes the Logits (probability distribution) output by existing LLMs during reasoning for refined post-processing.

We can break down the CER operation process into four rigorous steps, which interlock to transform unstructured natural language into computable mathematical scores.

3.1 Reasoning Path Generation

First, we need to let the model generate multiple possible solutions for the same problem. Similar to Self-Consistency, we typically set a higher sampling temperature (e.g., or ) to allow the model to be creative and generate different reasoning paths.

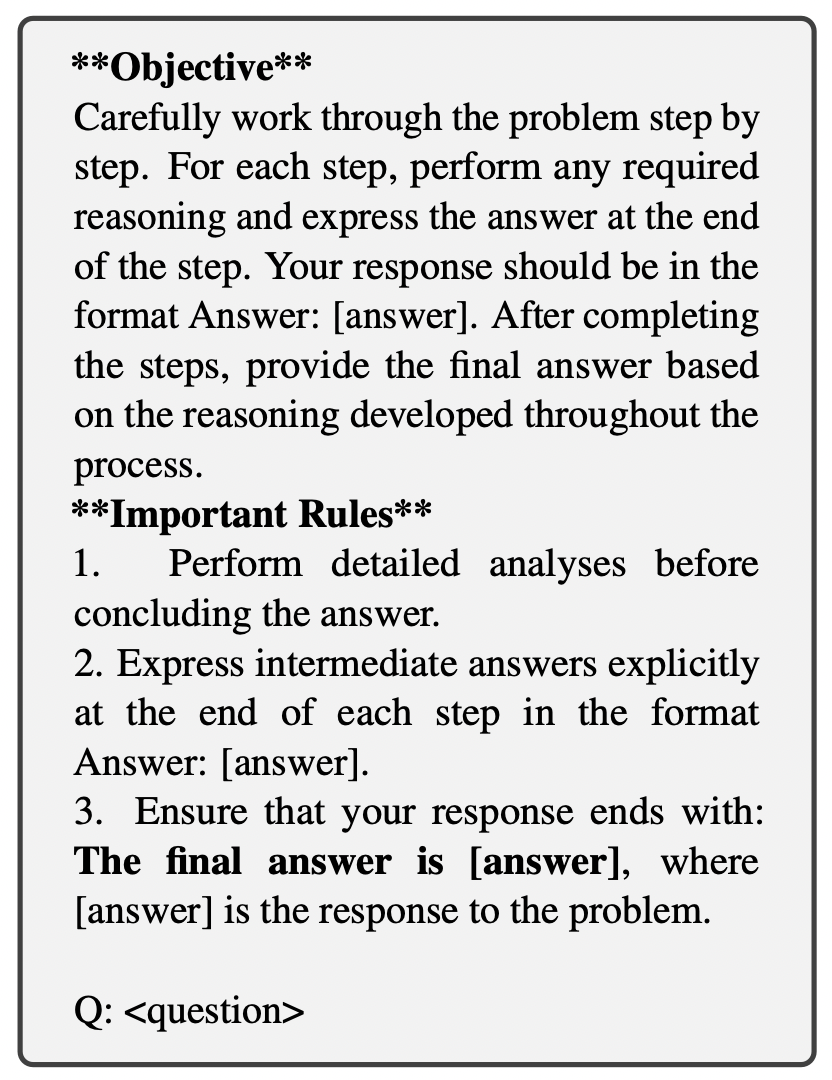

However, CER makes a key modification here: Prompt Design.

To enable the program to automatically extract key points later, we must establish a “contract” with the model. Through a carefully designed Prompt (as shown in the figure below), we require the model to output intermediate answers in a specific format at the end of each reasoning step.

- Math Tasks: Requires outputting

Answer: [value]. - QA Tasks: Requires outputting

Response: [entity/phrase].

The purpose of this is to transform the unstructured Chain-of-Thought (CoT) into “semi-structured” data, allowing us to easily extract information using Regular Expressions (Regex) later.

3.2 Identifying Critical Tokens

This is the watershed between CER and traditional methods. Traditional methods calculate the Log-Likelihood of the entire generated sentence, but CER believes: Most words in a sentence are noise (fillers); only the reasoning nodes are signals.

In implementation, we use Regex to grab the tags defined in the Prompt (such as Answer: or Response:) and lock onto the content following them as “keywords.”

- Math Tasks: Focus on Numerical values. For example, “100”, “5”, “125” appearing during the calculation.

- Open-Domain QA: Focus on Proper Nouns. For example, names, places, or specific entities.

Through this filtering mechanism, we exclude high-probability but uninformative words like “Therefore”, “We calculate”, “is equal to”, ensuring our confidence score purely reflects the model’s certainty regarding the “reasoning results.”

3.3 Confidence Estimation

Once the keywords are locked, we need to calculate scores. This is divided into two levels: Word Level and Path Level.

3.3.1 Word-Level Aggregation (): From Token to Word

A keyword (e.g., “125”) may consist of multiple Tokens (e.g., Token IDs [1, 2, 5]). We need a function to calculate the overall confidence of this word.

The paper verifies that the most effective method is to calculate the Joint Probability, which is multiplying the probabilities of all constituent Tokens:

Multiplying multiple decimals (probabilities) directly can cause Underflow (becoming 0) in computers due to extremely small values. Although keywords are usually short and the risk is low, in rigorous programming implementations, we typically use the Log-Sum-Exp trick:

We first take the Log of the probabilities (turning them into negative numbers) and sum them (which is numerically very stable), then use Exponential to restore them to the [0, 1] probability space. This is mathematically equivalent but safer in engineering.

3.3.2 Path-Level Aggregation (): From Word to Path

A reasoning path contains multiple steps, each with an intermediate answer. We need a function to synthesize these intermediate scores into a score for the entire path, .

CER uses the Linearly Weighted Mean.

Where is the step sequence number (Step 1, Step 2…), and is the confidence of the key answer in the -th step.

Why weight it? Because reasoning is cumulative. Step 1 is usually just understanding the question and is simpler; whereas the final Step often relies on the correctness of all previous steps. If the model is very confident in the last step, it usually implies that the preceding foundation is solid. Therefore, steps closer to the final answer carry more weight.

3.4 Confidence-Weighted Aggregation

The final step is to select the final answer from the paths.

- Self-Consistency (Baseline): Simply counts how many times each answer appears (Count Voting).

- CER (Our Method): Calculates the sum of confidence of all paths supporting that answer.

We ultimately select the answer with the highest score .

In this way, if a path derives a certain answer but is hesitant (low confidence) during the intermediate process, its contribution to the total score will be small; conversely, a path that is logically clear and confident at every step will have a decisive impact on the final decision.

4 Experimental Results

In scientific research, experimental data is not just to prove “scores got higher,” but more importantly to verify if our initial hypotheses hold true. This paper conducted extensive experiments covering different model scales (from 3B to 8B) and different types of tasks (Mathematical Reasoning and Open-Domain QA).

We summarize the experimental results into the following noteworthy points:

4.1 Overall Performance: CER Outperforms Baselines

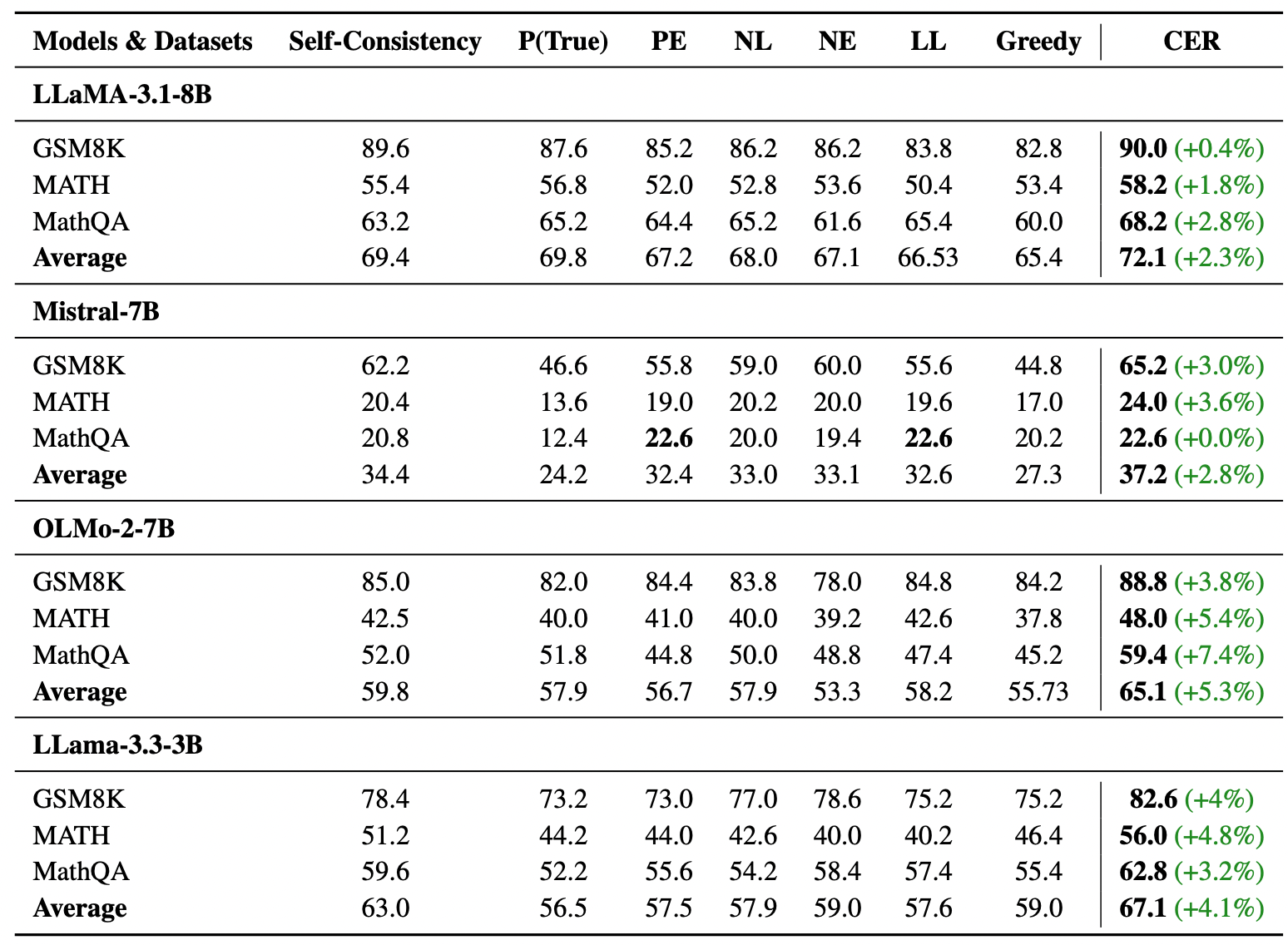

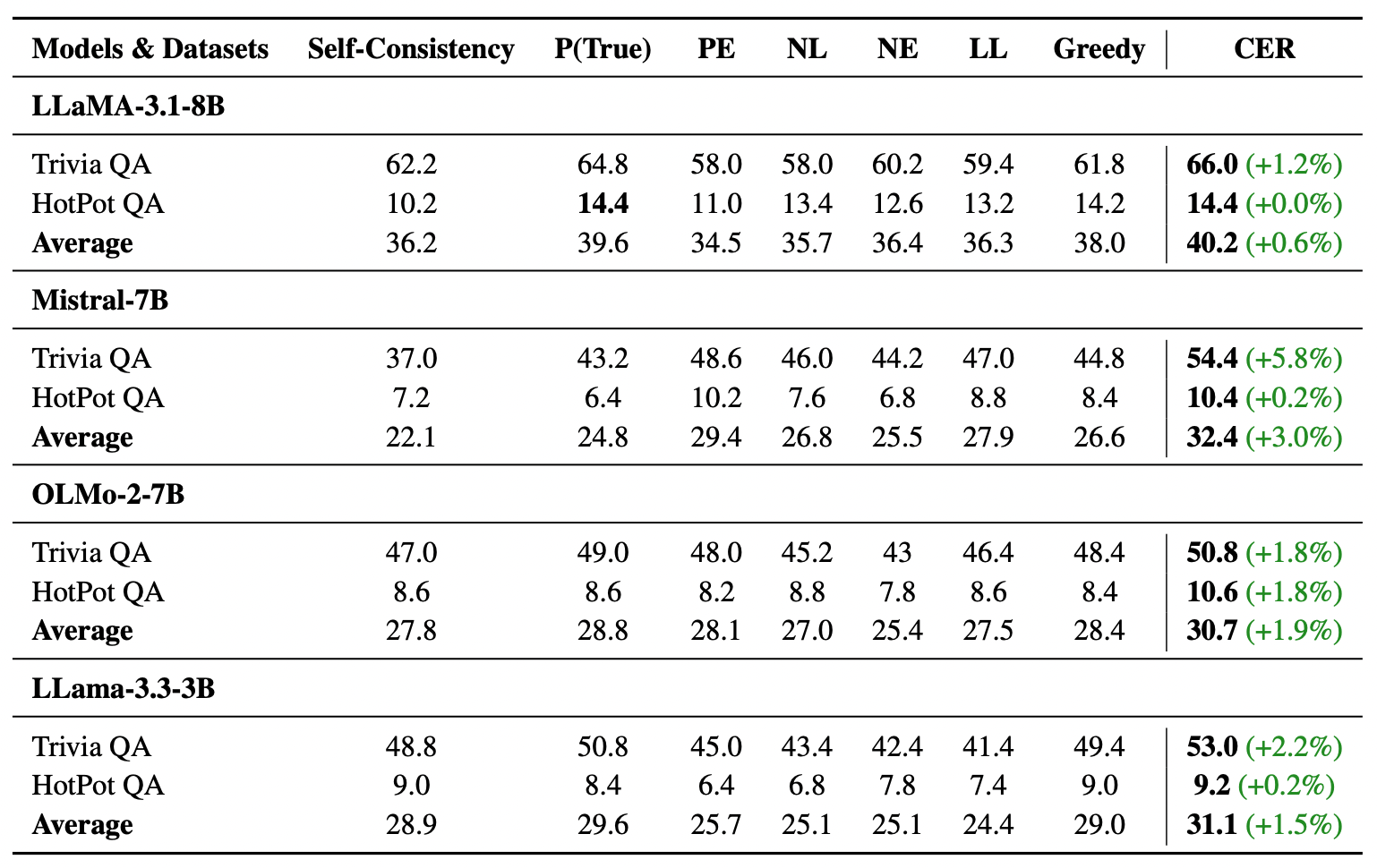

The authors tested on three math datasets (GSM8K, MATH, MathQA) and two QA datasets (TriviaQA, HotPotQA). The comparison baselines included Greedy Decoding, Self-Consistency (SC), and other probability-based statistical methods.

From the table, we can observe:

- Consistent Improvement: CER achieved better results than the Baseline across all datasets and models.

- Significant Difference: On harder datasets like MathQA, the improvement magnitude even reached 7.4% (OLMo-2-7B).

4.2 “Weak Models” and “Hard Tasks” Benefit More

This is a very interesting finding. If we look closely at the data, we see that the magnitude of improvement is not uniform.

- Strong Models: For powerful models like Llama 3.1 8B, the improvement on relatively simple GSM8K tasks is smaller (about 0.4%). This is because strong models are already confident and have very low error rates, leaving limited room for improvement.

- Weak Models: For models with fewer parameters or weaker reasoning capabilities (such as OLMo 2 7B or Mistral 7B), the improvement brought by CER is enormous.

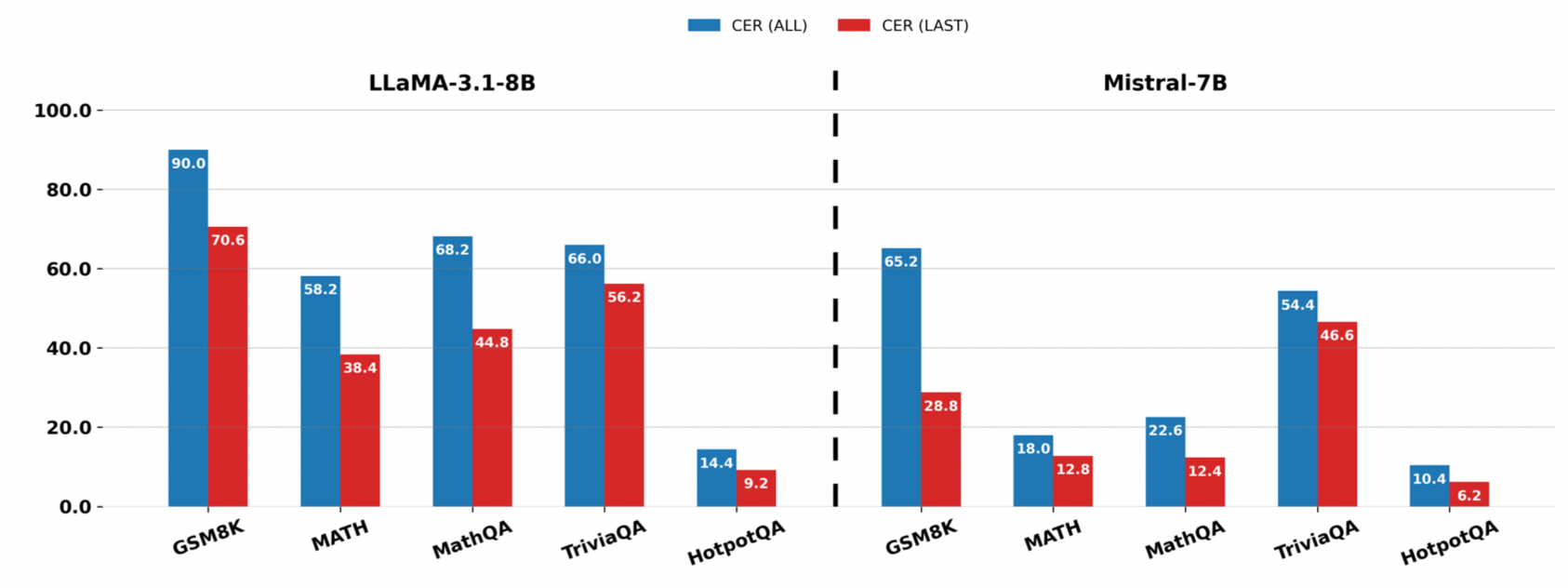

4.3 Core Hypothesis Verification: “Process” Matters More Than “Outcome”

This is the most scientifically important experiment (Ablation Study) in the entire paper. To prove that “checking intermediate steps” is necessary, the authors designed a control group CER-LAST, which ignores the intermediate process and only calculates the confidence of the “final answer.”

The results, shown in the figure above, indicate that CER (Blue Bar) significantly outperforms CER-LAST (Red Bar) in all cases.

This directly proves the author’s core argument: A model might give a confident wrong answer (Overconfidence) at the end, but it often reveals hesitation during the intermediate reasoning process. If we only look at the last step, we will be deceived by the model; only by monitoring the entire journey can we catch these hidden errors.

4.4 Math vs. Knowledge QA: The Difference Between Reasoning and Memory

Comparing the results of Math tasks and Open-Domain QA, we find that CER’s performance on Math is generally more stable than on QA.

Specifically, the Llama 3.2 3B model improved by 4.1% on Math but offered almost no help on QA. This reveals the boundary of CER:

- Math is Logical Reasoning: CER can judge whether the logic is coherent through confidence.

- QA is Knowledge Retrieval: If the model parameters simply do not contain this knowledge (Knowledge Gap), no matter how much it reasons or calculates confidence, the model cannot get it right (this is known as “Hallucination due to ignorance”).

This tells us: CER is used to enhance “reasoning ability,” not to fill “knowledge inventory.”

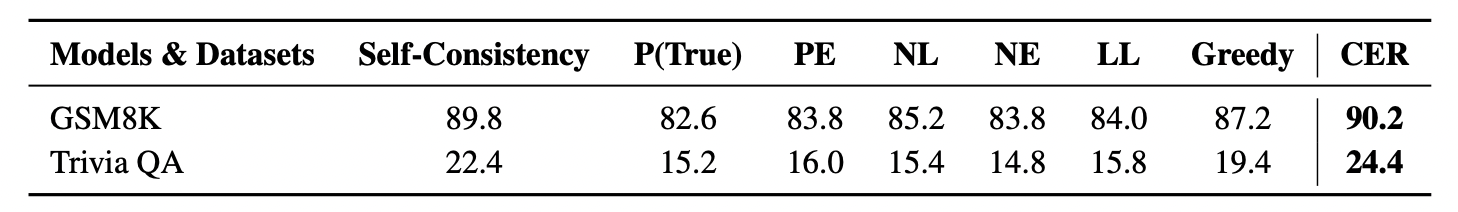

4.5 Applicable to the Latest Reasoning Models (DeepSeek-R1)

To verify the universality of the method, the authors also tested the recently popular DeepSeek-R1 variant (a reasoning model optimized via Reinforcement Learning). The results show that even for this model, which has been specifically fine-tuned for CoT, CER can still boost GSM8K accuracy from 87.2% to 90.2%.

This implies that the “confidence signals” captured by CER are inherent features universally present inside models, and this information remains available for exploitation even after RLHF training.

5 Conclusion

Congratulations on completing the deep dive into this paper! Reviewing the entire architecture of CER (Confidence Enhanced Reasoning), we can see that while its technical implementation is not complex, the insight behind it is profound.

This paper gives us an important revelation: In the reasoning of Large Language Models, the quality of the “process” determines the reliability of the “result.”

The past Self-Consistency (SC) method solved the randomness problem through “majority voting,” but it ignored the subtle voices inside the model—the hesitation and confidence hidden in the Logits. Through a simple and elegant hypothesis—“Only look at key steps, ignore filler noise”—CER successfully proved that we don’t need expensive extra training; we just need to intelligently interpret the signals the model has already given to significantly improve reasoning accuracy.

CER teaches us two valuable lessons for engineering practice:

- The Power of Structured Data: By forcing the model to output

Answer:orResponse:tags through Prompts, we can transform unstructured natural language into semi-structured data. This is a key technique for improving system controllability without changing the model architecture. - Logits are an Undervalued Gold Mine: The model’s raw output (Logits) contains much richer information than the final text. Learning how to separate the wheat from the chaff (calculating only the probability of key Tokens) is an effective way for us to squeeze more performance out of existing models.

Finally, although CER performs brilliantly on mathematical reasoning, experiments also show its limitations on pure knowledge retrieval tasks. This reminds us that confidence can filter “logical fallacies,” but it cannot conjure “missing knowledge” out of thin air.