Google's "Free Lunch" for LLMs: How Prompt Repetition Fixes Attention Bottlenecks with Zero Latency

1 Introduction

Welcome to the paper note for “Prompt Repetition Improves Non-Reasoning LLMs”. Published by the Google Research team in December 2025, this paper presents a discovery that is unbelievably simple yet incredibly inspiring.

- Paper Link: arXiv:2512.14982

In AI research, we often pursue complex model architecture modifications or expensive training processes to enhance performance. However, this paper goes the opposite way, telling us: “Sometimes, just copy-pasting the input Prompt once can yield significant performance gains.”

This note will guide us from the Causal Attention of Transformers, understanding why models “cannot understand” a single input, and why Prompt Repetition can be seen as a clever means to simulate Bidirectional Attention on Decoder-only architectures.

The core value of this note lies in clarifying the following three key points (TL;DR):

- Methodology: Changing the input from to .

- Principle: Utilizing the repeated input, allowing Tokens to “see” the full context, thereby repairing the representation quality of Key/Value.

- Benefit: This is a “Free Lunch”. It leverages the parallel computing characteristics of GPUs to improve accuracy without increasing inference latency.

2 Problem Definition

The core problem this paper attempts to solve stems from the fundamental architectural limitations of current mainstream Large Language Models (LLMs, such as GPT-4, Gemini, Llama). These models mostly adopt the Transformer Decoder-only architecture, which means they have a unidirectional “vision defect” when processing information.

The challenge this paper wants to address can be summarized as:

How can we overcome the unidirectional attention bottleneck of causal models and endow them with understanding capabilities similar to “bidirectional attention,” without changing the model architecture (Black-box compatible) and without increasing generation delay (Zero latency overhead)?

2.1 The Causal Attention Bottleneck

In the Decoder-only architecture, the model is Causal. This means that when the model generates or processes the -th Token in a sequence, it can only “see (Attend to)” tokens at positions , and cannot see future tokens .

This leads to a fundamental problem: The Representation Quality of a Token is limited by the point in time it appears.

Let’s recall the mathematical intuition we discussed before: In every layer of the Transformer, the Attention mechanism operates as follows:

When the model processes tokens at the beginning of a sequence, the Key () and Value () generated only contain information prior to that point in time. This means these early tokens are encoded in a state of “knowing nothing about the future.”

2.1.1 Case Analysis: Ambiguity Issues

To make this concrete, look at the following example:

Input sentence:

"The bark was rough. <Question> ..."

- Early Token Processing: When the model reads the word

"bark", it only sees"The bark". At this moment, the model cannot determine if “bark” refers to the sound a dog makes or the skin of a tree. Therefore, the Key/Value vectors it generates might be a vague mixture. - Late Token Processing: When the model reads

"rough"later on, although this last Token knows the sentence is about tree bark, it must look back to Attend to the information of"bark". - Noisy In, Noisy Out: Although the last Token has a global perspective, the raw material it grabs (i.e., the vector of

"bark") is early-generated, low-quality, and ambiguous. This limits the model’s ultimate understanding capability.

2.2 Sensitivity to Input Order

Due to the unidirectional attention limitations mentioned above, models become extremely sensitive to the order of the Prompt. This is referred to in the paper’s experiments as the challenge of “Options-first” vs. “Question-first”.

- Context/Options First (

<Context> <Question>): When the model reads the Context, it doesn’t know what the Question is yet. Therefore, it cannot specifically extract information relevant to the question (Key/Value are non-specific). - Question First (

<Question> <Context>): The model sees the question first, theoretically allowing for better focus when reading the Context. However, as the Context gets longer, the model might forget the preceding question, or its attention might be scattered.

2.3 The Trade-off

Before Prompt Repetition, we typically faced two solutions, both with obvious flaws:

Chain-of-Thought (CoT): Letting the model “Think step by step” or restate the question first.

- Pros: Through the generation process, the model forces itself to re-process information, solving the representation problem mentioned above.

- Cons: Expensive and slow. This increases the number of generated Tokens (Decode phase), directly leading to increased Latency and API costs.

Bidirectional Attention / Prefix LM: Like BERT or T5, allowing Input Tokens to see each other.

- Pros: Fundamentally solves the representation problem.

- Cons: This requires changing the model architecture or training objectives. For off-the-shelf Decoder-only models accessible only via API (like GPT-4, Claude 3), this is an impossible task.

This is the most essential and exciting part of this paper for engineers. Because usually in the AI field, “better results” often means “slower computation” or “more complex architecture.” But Prompt Repetition breaks this convention.

Let’s dive deeper into the specific implementation of this method and the system mechanics behind it.

3 Method Introduction

The method proposed in this paper is conceptually intuitive to the extreme, and can even be summarized in a single line of code: Copy the user’s input Prompt verbatim.

3.1 Core Operation: Prompt Repetition

Suppose the user’s original input is , which might contain a long article (Context) and a question (Question). In standard practice, the model’s input sequence is .

But in Prompt Repetition, we transform the input into:

Which is the form <QUERY><QUERY>.

3.1.1 Why does this work? (Analyzed from an Attention perspective)

Let’s label the repeated input sequence into two parts: the first pass and the second pass .

(The “Context” Provider): When the model processes , it acts as usual, limited by causal attention, knowing nothing about subsequent information. The Key/Value representations produced here might be imperfect.

(The “Context-Aware” Reader): This is where the magic happens. When the model starts processing every Token in , since the Causal Mask allows it to see all preceding Tokens, every position in can fully “see” the entire .

This creates a Pseudo-Bidirectional Attention effect:

- In , Tokens originally at the beginning (e.g., Context) can now query Tokens at the end of (e.g., Question) via the Attention mechanism.

- This means the Key/Value Pairs generated in are high-quality representations that have “seen the full text.”

- When the model finally generates the answer, it relies heavily on this high-quality information from , thereby making accurate predictions.

<Context><Question> or <Question><Context>, after repetition, the part ensures “mutual care.” Developers no longer need to worry about how to arrange the Prompt, greatly enhancing system Robustness.3.2 Variations & Ablations

To prove this effect isn’t a coincidence, the authors designed several variations for testing. This part is very helpful for us to understand “why repetition.”

Prompt Repetition:

- Format:

\( <QUERY><QUERY> \) - Conclusion: This is the main method recommended by the paper, effective, stable, and efficient.

- Format:

Prompt Repetition - Verbose:

- Format:

\( <QUERY> \text{Let me repeat that:} <QUERY> \) - Logic: Testing if the model needs natural language transitions like a human.

- Conclusion: Effectiveness is about the same as standard repetition, but with more tokens, so the cost-performance ratio is slightly lower.

- Format:

Padding:

- Format:

\( ...(\text{dots})... <QUERY> \) - Logic: We need to verify: Does the performance boost come from “repeating meaningful information,” or simply because “the input got longer, giving the model more computational space”?

- Conclusion: Padding is completely ineffective. This proves the source of improvement is indeed the “bidirectional attention simulation” we deduced, not merely increased depth.

- Format:

3.3 Why is this a “Free Lunch”?

You might worry: “The input length doubled; won’t it get slower?”

The answer lies in the difference between the two stages of the LLM inference process: Prefill and Decode.

3.3.1 Prefill Phase (Processing Prompt)

- This is the stage where the model reads

<QUERY><QUERY>. - Characteristics: GPUs can be highly Parallelized. The time difference between calculating the Attention Matrix for 1000 Tokens versus 500 Tokens simultaneously is minimal (usually in the millisecond range).

- Impact: Although we doubled the input, the extra time cost for this part is almost imperceptible to the user.

3.3.2 Decode Phase (Generating Answer)

- This is the stage where the model spits out the Output one word at a time.

- Characteristics: This is a Serial process, limited by Memory Bandwidth, and is the main culprit for LLM latency.

- Impact: Prompt Repetition does not change the semantics of the Prompt (e.g., it doesn’t ask to “Think step by step”), so the length of the Output generated by the model remains unchanged.

3.3.3 Summary Comparison

| Method | Input Length | Output Length | Prefill Time | Decode Time | Total Latency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Short | Short | Fast | Fast | Low |

| CoT (Reasoning) | Short | Long (Main cause of slowness) | Fast | Slow | High |

| Prompt Repetition | Long (Absorbed by parallelization) | Short | Fast (Slight increase) | Fast | Low (Close to Baseline) |

This is why the authors dare to boldly claim this is a “Free Lunch”: We utilize the excess computing power of the GPU during the Prefill phase in exchange for the model’s precise understanding of the content, without sacrificing user wait time at all.

4 Experimental Results

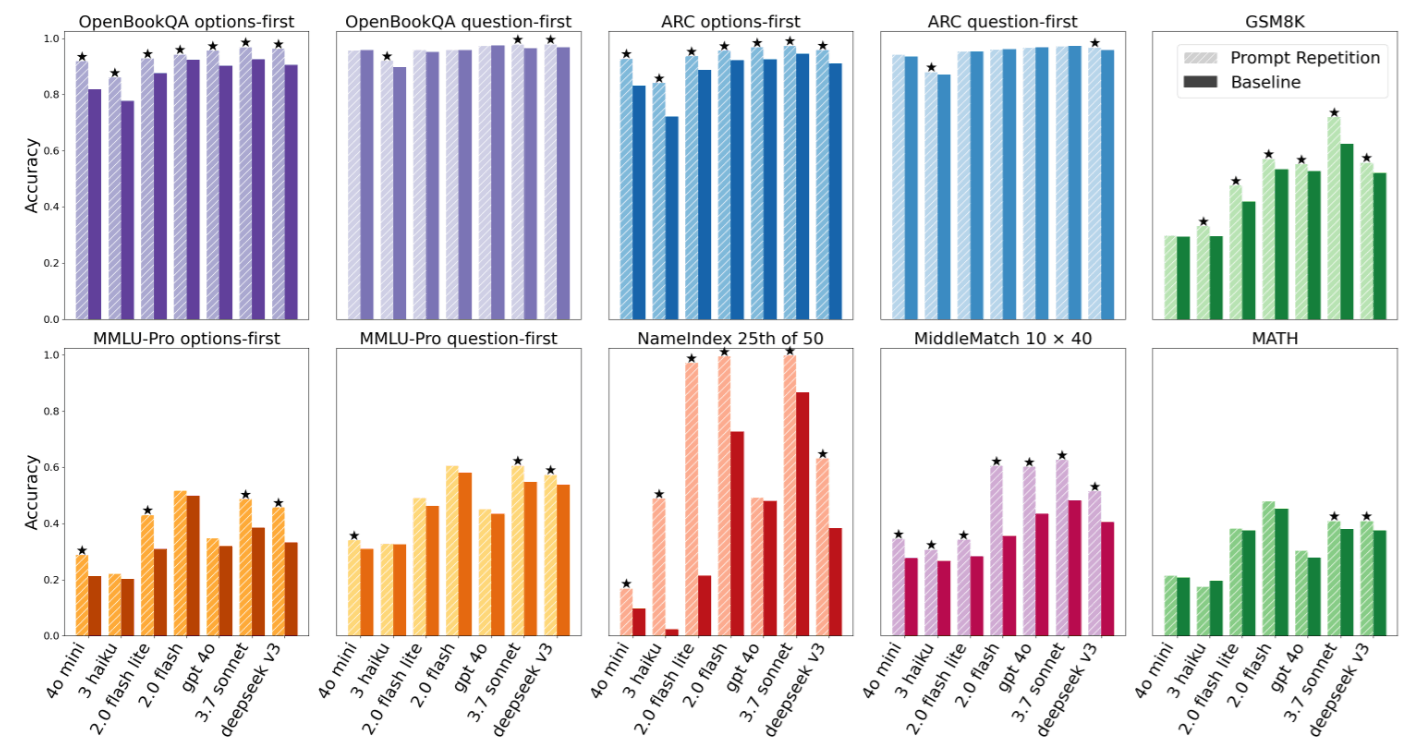

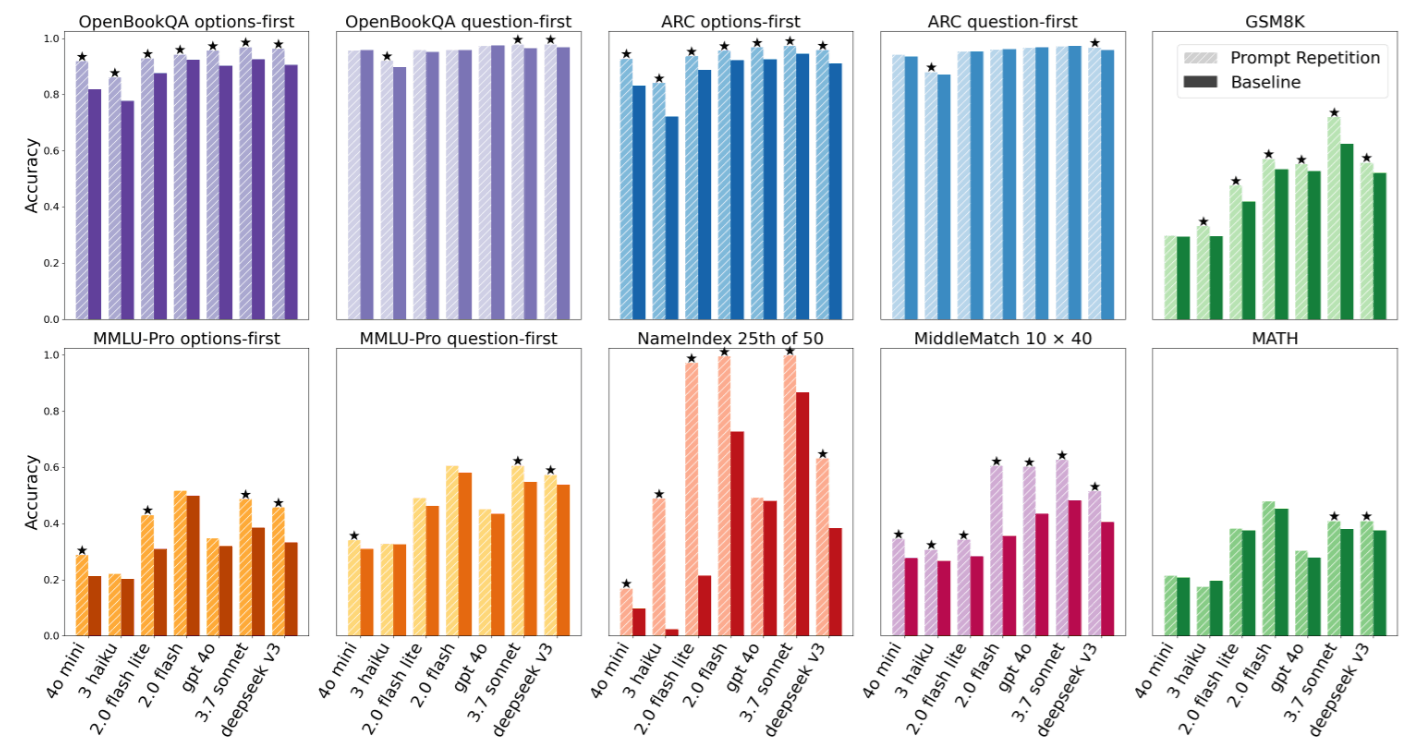

Here are the 5 most noteworthy experimental findings, which not only verify the effectiveness of Prompt Repetition but also reveal deep characteristics of Transformer operations.

4.1 Amazing “Zero Defeat” Record

First, the most shocking result is the universality of this method. The authors used the McNemar test to evaluate statistical significance (setting ).

- Record: across a total of 70 “Model-Task” combination tests, Prompt Repetition achieved an overwhelming score of 47 wins and 0 losses (the rest were ties/no significant difference).

- Significance: This is extremely rare in the machine learning field. Usually, a trick might work for GPT but not for Claude. But Prompt Repetition spans across different model architectures and parameter scales.

4.2 Powerful Repair of “Input Order”

We mentioned in the “Problem Definition” that LLMs are usually sensitive to Prompt order. The paper compared two formats:

- Options-first:

<Options> <Question> - Question-first:

<Question> <Options>

Experiments found that in the Baseline, Options-first usually performed poorly (because it doesn’t know the question when reading options). However, once Prompt Repetition was used:

- The performance of

Options-firstreceived a huge boost. - Its performance even caught up with or surpassed the originally superior

Question-first.

This confirms our theory: Repeating the input lets the model know what the question is when reading the options for the second time. This means developers no longer need to worry about how to place the Prompt; Prompt Repetition brings extremely high Robustness to the system.

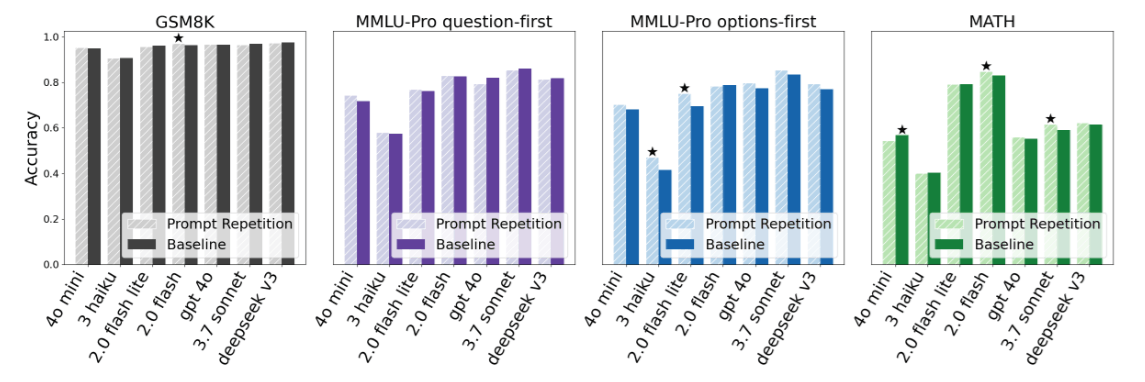

4.3 Empirical Evidence of “Free Lunch”: Unchanged Latency and Length

Please refer to the experimental data in Figure 2 of the paper:

- Output Length: Highly consistent between the two. This proves Prompt Repetition does not trigger the model to generate long-winded explanations like CoT.

- Latency: Almost flat. Even if the input is twice as long, the End-to-End latency barely increases.

4.4 4. Reasoning vs. Non-Reasoning Tasks

To explore the boundaries, the authors conducted an interesting control experiment: forcing the model to turn on “Think step by step” (CoT).

- Result: After turning on CoT, the effect of Prompt Repetition became “neutral to slightly positive” (5 wins, 1 loss, 22 ties).

- Interpretation: This perfectly corroborates our previous deduction.

- Baseline + CoT: The model repeats/thinks during the Output phase itself, fixing the representation problem.

- Repetition + CoT: Although harmless, since the model can already fix itself, the marginal utility of us repeating it at the Input end diminishes (Diminishing Returns).

This tells us: Prompt Repetition is best suited for tasks that “require precise understanding but do not need complex multi-step reasoning” (such as information extraction, reading comprehension).

4.5 The “Microscope Effect” of Custom Tasks

To prove the effect isn’t luck, the authors designed two extreme “lookup tasks” (Appendix A.3), the most classic being the NameIndex task.

- Task: Given a list of 50 names, ask: “Who is the 25th name?”

- Gemini 2.0 Flash-Lite’s Performance:

- Baseline: 21.33% (Almost a blind guess).

- Prompt Repetition: 97.33% (Near perfect).

Why is the gap so huge?

Because in the Baseline, when the model reads the 25th name, it doesn’t know the question is “find the 25th,” so it doesn’t specifically remember that name. By the time it reads the question, it’s too late to look back (causal limitation). But Prompt Repetition allows the model to scan the list with the strong intent of “I want to find the 25th” when reading the second pass, naturally catching it accurately.

This extreme example is the most powerful evidence in this paper, proving that Prompt Repetition endows the model with capabilities similar to Random Access Memory.

5 Conclusion

Reading this paper is like unlocking an open secret that exists at the bottom layer of Large Language Models (LLMs). We started from an operation that seemed unbelievably simple—“Paste the Prompt again”—and ultimately delved into the most fundamental Causal Attention mechanism of the Transformer architecture.

5.1 What have we learned?

Inherent Defects of Causal Models: All Decoder-only models (like GPT, Gemini) suffer from “unidirectional vision.” Early Tokens cannot see future Tokens, leading to poor representation quality and excessive sensitivity to input order.

The Art of Trading Time for Space: Prompt Repetition cleverly utilizes the architectural characteristics of the Transformer by repeating information at the input end. It makes the Tokens in the second pass “omniscient,” able to look back and repair the ambiguity and vagueness in the first pass information. We exchange the computation of the Prefill phase (cheap, parallelizable) for the understanding power that originally only Bidirectional Attention models (like BERT) could possess.

A Free Lunch Exists: What impressed us most is its engineering efficiency. Because it utilizes the parallel computing power of GPUs, we achieved a significant improvement in accuracy with almost Zero Latency Overhead. This is extremely valuable in resource-constrained practical applications.

Connection with Reasoning Models: Through our discussion, we have gained further insight into why Reasoning Models trained with RL exhibit the emergent behavior of “restating the problem.” This is not accidental, but a survival strategy evolved by the model to overcome attention bottlenecks. Now, we just need to explicitly use Prompt Repetition to reproduce this advantage on non-reasoning models.